Making Time

Writers have the ability to manipulate time: to make it run backwards or forwards, to extend, compress or pause it. In this way, a writer can attempt to put into words the experience of time, which is never as predictable as measurements register. While the standard Gregorian calendar is based in part on celestial phenomena - the year is the earth’s rotation around the sun, the day the rotation of the earth on its axis, the month, roughly, the cycle of the moon - it is an invention, culturally wrought, with its origins in financial and religious schedules and their systems of control (the word ‘calendar’ comes from the Latin word ‘calends’, the first day of the month, when debts were due).

The grid of days, divided into weeks and months, is only one way of measuring time. Many other ways co-exist. Lifespans, lifetimes, memories, souvenirs. Cycles, repetitions, echoes. There are the patterns of weather and plant and animal behaviour that determine Aboriginal methods of marking time through the seasons. Where I live, on Gadigal country, this time of year is Bayin Gura in the Dharug calendar (as described in the Six Dharug seasons) - cool getting warmer, with the bright purple dianella berries out in profusion by the river. I notice them when I go walking and fight the urge to squeeze them to release their colour.

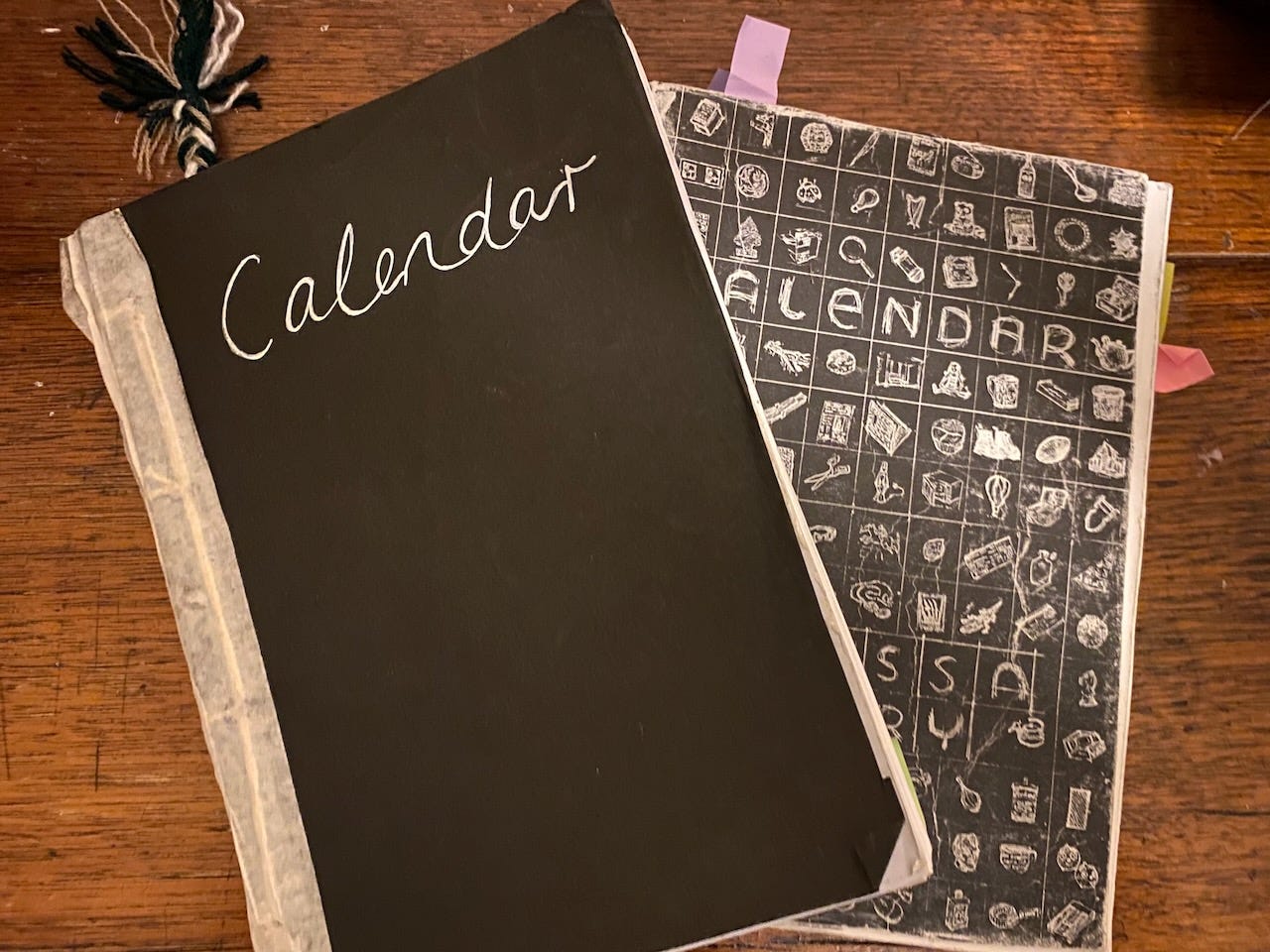

Calendars provide structure, giving form to cycles and repetitions. Within these systems, memory is an unpredictable experience of time: past in the present, emerging or interrupting, folding time back. Writing Calendar, one of the time relationships I was interested in was the memories connected to objects, be these personal, cultural or material memories, as a way of showing the complexity of time in any one moment.

Object of the Month

In each of these newsletters I will choose an object from the corresponding month in Calendar, and give its backstory. This month it is object 317, Giant Comb.

The comb came from the Marie Louise hair salon, which I wrote about in Mirror Sydney, an iconic Sydney business with a pink and purple 50s facade (the facade remains fronting a restaurant, the salon closed over a decade ago). When I went in for haircuts in the early 2000s it was a much for the experience of the salon, which was decorated with bright kitsch objects. A tame white cockatoo hopped around between the backs of the chairs while Nola, the hairdresser, snipped away.

When the contents of the Marie Louise were sold in 2013 I queued up outside, ready to acquire some mementos of the salon, which ended up being a bottle of blue rinse and a giant comb. When I was in the salon with Nola and the cockatoo my eyes had roamed around the objects decorating the mirrors: photographs, artificial flowers, the Giant Comb. I noticed the comb in particular because as a child I had seen such items as prizes at amusement parks and video arcades. They were the kind of useless, desirable prize I never had the manual skill to acquire. However now I was an adult and I had developed other skills that allowed for me to recoup such childhood disappointments.

As is the case with all of the objects I wrote about, there are many stories associated with each, and I could choose only one. The Marie Louise was only the start, and I ended up writing something different entirely about the comb in Calendar. But now when you read it, you will know where it came from.

Object Project

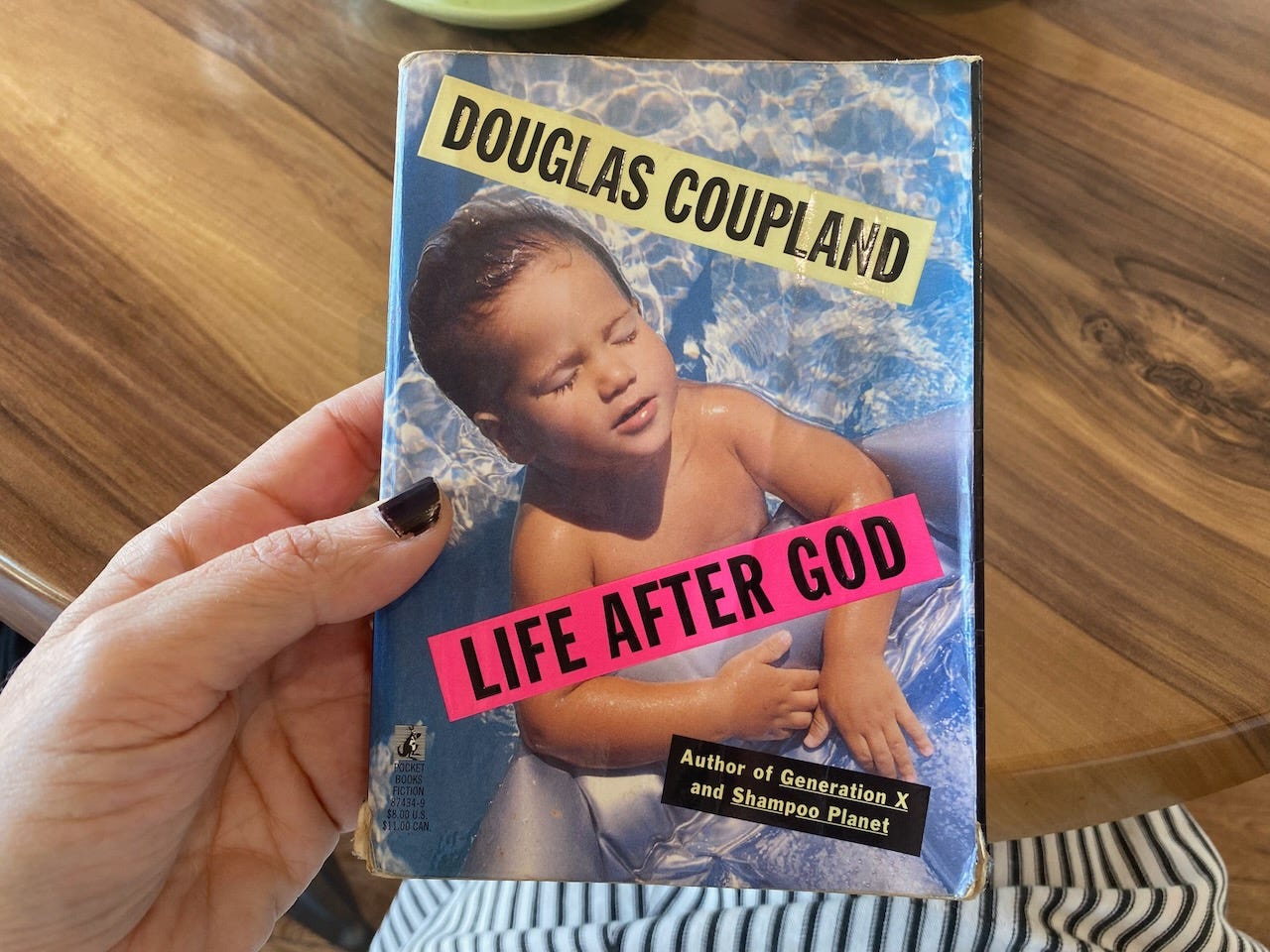

One of my favourite books is Douglas Coupland’s short story collection Life After God, which was published in 1994. This was a few years after his debut novel, Generation X, which popularised the term and propelled Coupland to stardom and the difficult position of being the spokesperson for an entire generation. The edition I had of Generation X was a big square book with wide page margins, in which were printed definitions of 80/90s neologisms (McJob, Sick Building Syndrome, emotional ketchup burst) and Jenny-Holzer-esque slogans (‘The Love of Meat Prevents Any Real Change’, and my favourite ‘We’re Behaving Like Insects’ which, to my now-embarrassment, I painted on a t-shirt and would wear around combined with a purple tie-dyed petticoat and 14-hole Docs with purple laces. But it was the 90s and I was a teenager, what choice did I have?)

Life After God was also published in an unconventional format, smaller than a usual paperback, a size that might fit in a pocket and be easy to carry around. On the cover was a photograph of a little kid in the chlorine-blue water of a backyard swimming pool, that seemed to me to be a resonance with the cover image of Nirvana’s Nevermind. In the late 90s I found a copy for $5 in the Half Back book exchange in Crows Nest (on a recent visit to Crows Nest I was astounded to find this shop much the same as it was thirty years ago - I had to check I was not wearing my homemade t-shirt and purple petticoat, in case I’d traveled back in time).

The stories of Life After God are about broken families, driving, shopping malls, nuclear fears, depression, and the transcendent power of everyday moments. Reading it back then felt like a transformation, a realisation that a quiet, observant way of being could be powerful. The stories put into words something of the way I often felt, that by paying close attention to the details around me and to my thoughts, I would break through to an understanding of the world and my place in it.

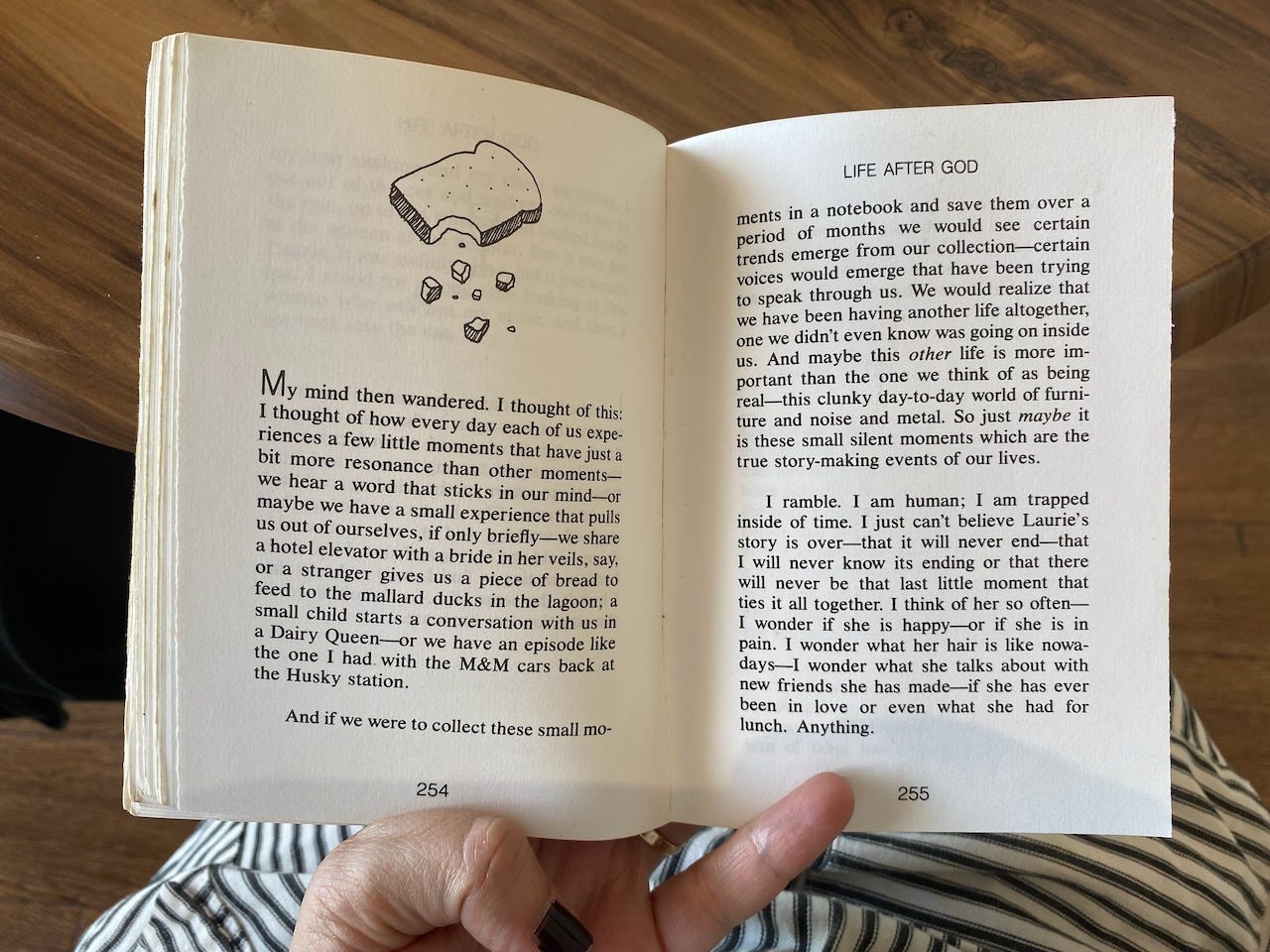

Every section, most of which were only a couple of pages or less, included funny little drawings, also by Coupland. They were carefully but simply sketched, and of scenes and objects like a piece of toast, a swingset, a balloon, a martini, a tent in the rain, a shopping centre parking lot, a camera, a broken vase, a packet of dental floss… mundane things around which each vignette or moment cohered. Later I found out that Coupland had originally made a DIY version of the book which he gave to friends, as described in this 1994 interview:

In search of a low-tech topic after writing his take on ambitious twentysomethings, Shampoo Planet, Coupland decided to explore - no kidding - the Irish potato famine of 1845 to 1847. But somehow, short stories "started popping out of me."

Coupland fashioned them into small books, bound at a nearby Kinko's Copies center, that he gave to friends. "I had no idea they'd become a book-book until near the end."

So that Life After God kept the feel of these "mini-books," Coupland asked that it remain smaller than the average hardback.

This made sense: the stories have a conversational tone, as if they were being told to a friend. There is a quietness and playfulness about them, a sense of a curious mind figuring something out, trying to match the precise detailing of the outer world with inner wisdom.

As well as the similarity with the combination of drawings and vignettes, the Kinko’s versions also reminded me of my work on Calendar. When I’m editing I like to make a book version of the manuscript, so I can read it that way rather than as a document.

This way, I can also carry it with me on my travels and read it in the way that I would any other book, as if it was written by someone else, an important distancing mechanism.

Other Projects

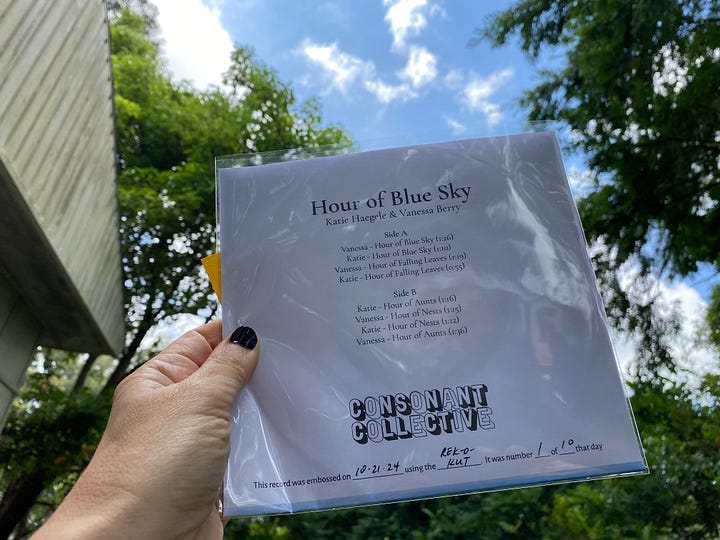

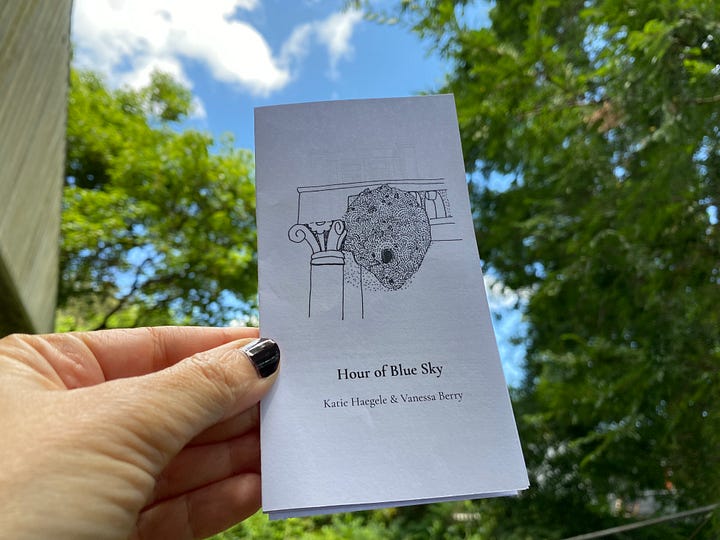

Earlier this year I visited my friend and writing partner Katie Haegele. We’ve made zines together (Winter Here, Summer Here; Mugs) but this was the first time we had met in person. Of course, we had to make a zine together to mark the occasion. The zine, Hour of Blue Sky, is made up of alternating autobiographical stories from us both, written after walking together in Laurel Hill cemetery, a hilltop cemetery above the Schuylkill River. Being together in the same space and time we wanted to write something that was of this moment. We liked the idea of a book of hours, short texts linked to particular times of day. I had also always liked the title of the Clarice Lispector novel The Hour of the Star, and we devised four different hours based on our time together: blue sky, falling leaves, nests, aunts.

As well as making the zine, we recorded the stories and pressed them as a 7” record, on the record cutting machines that Katie’s partner Joe uses for his record label Displaced Snail. Their machines are from the 1930s and 40s and were used to make recordings of live radio performances. Now such machines have been repurposed for making DIY vinyl records.

You can listen to and download Hour of Blue Sky here and buy a copy of the zine here.

*

Thank you for reading this month’s newsletter. I’ll be back again before the year is over.

Vanessa.

I like thinking of you enjoying Philadelphia and creating new work!

I loved reading this. In particular, It was affirming to read about Coupland's impact on you when you wrote. "...transformation, a realisation that a quiet, observant way of being could be powerful." I bet this is true for many introverts who are also writers and artists! Also, the strategy for construct books and your collaboration with Katie. I can't wait to listen to the entire recording and read the zine!